Sackett et al. (2022) recently questioned prior meta-analytic conclusions about the high IQ validity since the studies by Schmidt & Hunter decades ago. The crux of the issue is complex, but while the debate regarding range restriction correction is not (at least not completely) resolved yet, one thing is certain. The validity depends on the measure of job performance that is used in the meta-analysis. Maybe the importance of IQ has declined in recent years but the debate is not settled yet.

(updated: August 2nd 2024)

CONTENT

1. The groundbreaking study

2. The controversy

3. The choice of criterion (dependent) variable matters

1. The groundbreaking study

Sackett et al. (2022) found a meta-analytic validity of only .31, which is close to the estimate of .33 from Schmidt et al. (2016). When using alternative reliability estimates along with correction for indirect range restriction bias, this value of .31 rises to .36. In any case, this is much smaller than the estimate of .51 reported by Schmidt & Hunter (1998). Part of the explanation is that past meta-analyses applied range restriction (RR) correction strategies that lead to overcorrection, which ultimately overestimate the IQ validity. Correction for RR bias requires the unrestricted SD. The typical meta-analysis contains a mixture of incumbent-based concurrent designs (i.e., current employees) and applicant-based predictive designs, but only the latter design contains the information required to estimate the unrestricted range (SD) for the predictor of interest (predictive studies provide SDs of both the incumbents and applicants). This violates the assumption of random sampling of the unrestricted SD.

Here’s the problem. Meta-analyses typically include a great portion of concurrent studies. And the range restriction of the predictor x (e.g., IQ) is very small in concurrent studies but large in predictive studies. Therefore, applying RR correction from predictive studies on a set of studies composed mostly of concurrent study leads to a large overestimate of IQ validities. Their proposition is to not apply any correction or find a way to apply an appropriate correction.

In concurrent studies, RR can only be indirect because incumbents had already been hired prior to the study using some method (predictor) z other than the focal predictor x (e.g., IQ). If RR is indirect, there must be a strong correlation between z and x (i.e., rzx) for there to be substantial restriction of range on x. But because they found (Table 1) that the intercorrelation between predictors is at best rzx=.50 (but often lower), assuming a selection ratio larger than .1 (which they find plausible), the restricted SD from indirect RR should be .90 or greater. This means correcting for restricted SD from indirect RR will have a small effect. But in predictive studies, RR can be direct and indirect. Under direct RR, though, the SD of predictor x is restricted quite substantially. This will create a strong correction factor.

Sackett et al. (2022) argued that the restricted SD of .67 used in Hunter (1983) and other studies is too small, and is only possible if there is a large correlation between the predictor X and selection Z (rzx = >.9) paired with an extreme selection ratio. They find it unlikely that virtually all firms choosing to participate in a validation study of the GATB (which dominated Hunter’s samples) used another highly correlated cognitive ability test in initial selection, and used it with an extreme selection ratio.

To get a validity of .31, they did not correct for range restriction (Table 2). They reported a value of .59 if RR correction is applied although they do not find it credible. When assuming plausible values of rzx (<.50) and very low selection ratio, their validity of .31 rises to .34.

In their discussion, they insist on the importance of separating concurrent and predictive study. One reason is that the concurrent validities may not accurately reflect predictive validities if experience varies across current employees.

One particular concern is the range restriction on the criterion variable (job performance). High performers may have been promoted out of the job and low performers may have been dismissed. This reduced range will negatively impact validity estimates. But the probability of dismissal and promotion depends on performance, which creates indirect RR. Sackett et al. (2022) believe that the impact of RR is low due to the low interrater reliability of job performance.

Sackett et al. (2023a) supplemented their earlier analysis with some arguments. They argued against applying a uniform correction to all studies in a meta-analysis. For predictive studies, one should use both applicant and incumbent predictor SDs. For concurrent studies, one should use correction based on knowledge of the correlation between the predictor of interest and predictor used to select employees.

They hypothesize that the lower validity of IQ in newer data also reflects the reduced role of manufacturing jobs (which dominated the Schmidt and Hunter data) in the 21st century economy and the growing role of team structures in work, resulting in a growing share of less cognitively loaded interpersonal aspects of work, such as citizenship and teamwork.

Owing to these new findings, they believe that IQ should be given a smaller weight in a regression model involving multiple predictors. According to them, giving a weight of zero for cognitive ability based on their updated validity estimates reduces validity by only .05 (from .61 to .56). They still admit that, in jobs where lengthy and expensive training investments are made, cognitive ability remains the best predictor.

2. The controversy

Ones & Viswesvaran (2023) argued that Sackett et al. (2022) did not use real-world data to probe the degree of range restriction (RR) in concurrent studies of each predictor, and that concurrent and predictive study designs have similar range restrictions, based on several reports. They do not believe that Hunter et al. (2006) overcorrected for range restriction because they primarily use GATB datasets, for which they use means and SDs (necessary for RR) provided by the GATB manual. They are also concerned by the restricted datasets (from 2000s onwards) being dominated by studies which were designed to show contrary findings and/or incremental validity of novel predictors over IQ. They disagree with Sackett et al.’s assertion that job knowledge tests and work sample tests are the top predictors because IQ is a primary causal determinant of both and is highly correlated with acquiring domain specific knowledge. And while Sackett et al. argued that study and practice are important determinants of knowledge acquisition and skill development, meta-analyses showed that practice is not an important predictor of expert performance in most cases (Hambrick et al., 2014; Macnamara et al., 2014; Platz et al., 2014).

In their response, Sackett et al. (2023c) argue that concurrent and predictive studies have very different range restriction only if the predictor is used for selection among predictive studies. Moreover, not all studies in the GATB dataset used GATB for selection to justify range correction for all, and some tested newly hired employees while others tested incumbents. They reject Hunter’s (1983) conclusion because the range restriction in recent studies is much smaller compared to older studies. Finally, they believe that recent studies are not biased because they find no validity differences when partitioning studies that (a) examined and found incremental validity, (b) examined and did not find incremental validity, and (c) did not address incremental validity.

Oh et al. (2023a) showed that Sackett et al.’s assumptions are untenable. First, they demonstrate that the correlation between the predictor X and selection Z (rzx) can be very high, even as high as .90 after correcting rzx for measurement error, implying large indirect range restriction (RR). Second, they report several studies showing that selection ratios of .30 and lower are not rare at all. Third, that if realistic selection ratios (i.e., lower than .30) were used, the restricted SD would be lower than .90, and even close to Hunter & Hunter’s (1984) value, and in this case, applying range correction has a much greater impact than reported by Sackett et al. (2022). Fourth, they faulted Sackett et al. for using the Case IV correction that assumes that the selection variable influences the criterion performance only through the predictor (e.g., IQ), despite this assumption being likely violated. They argue that Case V is the preferred method. They further show that using Case IV instead of Case V correction, coupled with no correction for range restriction, greatly underestimated the validity estimate of IQ. Finally, even considering Sackett et al.’s own reasonable estimates of rzx and selection ratio, not correcting for range leads to non-trivial difference (.31 with no correction and .38 with correction).

In response, Sackett et al. (2023b) argued that the new predictors used in new studies are sought to have small correlations with predictors already in use, which is why they suspect rzx to be small. They disagree with Oh et al. (2023a) statement that high rzx is widespread, since these scenarios will be quite uncommon in concurrent studies and that firms want to avoid redundant predictors (which will result in low rzx). They do not regard rzx=.90 after correction for artifacts as possible because most of their reported rzx values were already corrected for measurement error and range restriction. They also disagree with Oh et al. recommendation of using Case V correction instead of Case IV, because Case V requires data on the restricted and unrestricted SDs for both the predictor X and criterion Y. But in personnel selection settings, the unrestricted SD of Y is generally unknown. Oh et al. were able to apply Case V only because their analysis was a simulation that uses assumed (rather than real) values. Furthermore, Oh et al.’s finding of larger estimate for Case V correction rests on the assumption of a validity for the selection Z being rzy=.50, but if this true value was actually low, the difference in validity estimates between Case V and IV is almost identical.

Oh et al. (2023b) observed that Sackett et al.’s (2022, 2023a) recommendation implies that all concurrent studies are alike in terms of the degree of range restriction (RR), yet the evidence shows that the degree of RR varies by predictor, with the restricted SD being smaller for cognitively-loaded selection procedures than for non-cognitive selection procedures. Moreover, they cite Morris (2023) who argued that even predictive studies will typically use multiple predictors, the consequence of which is that the focal predictor will be correlated with the selection variable, therefore creating indirect RR. Finally, they proposed a simple method for applying RR in concurrent studies: comparing the job-specific applicant-based SD across various jobs to the applicant-based national workforce norm SD.

In response, Sackett et al. (2023c) said that rzx will generally not reach the level needed for indirect restriction to have a large effect (i.e., about rzx = .70 or higher) because x was not used in selecting the job incumbents, and the correlation between different selection procedures (e.g., x and z) is generally .50 or lower. However, in predictive studies, x often will be used to hire applicants and be part of a battery of other predictors used to select applicants. In this case, the correlation between x and z can be high, when the intercorrelation between predictors is higher or when the number of predictors is smaller, and even higher when both conditions apply. They agree with Oh et al. (2023a) that concurrent and predictive study designs should have similar RR, only if the test is not used for selection in predictive design. Yet selection often occurs. Finally, they believe that the restricted SD of .67 is too low for the amount of RR in the set of concurrent studies in Hunter’s meta-analysis. Based on Salgado and Moscoso’s (2019) reanalysis of the GATB studies examined by Hunter, they obtained a restricted SD of .86, and using this same approach of pooling across incumbent samples to estimate the applicant pool SD in the newer, procedurally equivalent GATB studies, they get an applicant pool SD that is similar to the incumbent SD, signaling very limited range restriction.

Cucina & Hayes (2023a) raise multiple questions. They observe that Hunter’s (1983) approach of using the national workforce SD for the GATB instead of local job-specific applicant SDs only slightly lowers the applicant pool SDs, which would invalidate Sackett et al.’s critique. They also argued that Sackett et al. did not provide a solid explanation (e.g., educational requirements or self-sorting) for why a restricted SD .67 occurred in Hunter’s study. The jobs from the GATB studies were mostly entry-level and only 4% of the studies had jobs requiring a college/advanced degree. Because people cannot estimate their cognitive ability well, it is unlikely they would self-sort into jobs based on IQ.

They further add that supervisory rating (the criterion used by Sackett et al.) is a flawed measure as it may not reflect employee’s job knowledge. Changing the criterion matters: the validities of various IQ tests are much higher when work simulation rather than supervisory ratings is used as the criterion (Table 2). Not including IQ results in a predictor deficiency, because IQ is the best predictor of transfer of training specifically for maximal performance (Huang et al., 2015). Perhaps the most important point is that multiple studies show that the IQ validity is much higher when the criterion used is hands-on performance test (HOPT) scores rather than supervisory ratings.

Cucina & Hayes (2023a) also raise several paradoxes. Why IQ predicts firearm proficiency (Cucina et al., 2023b) better than overall job performance: Higher validity for a psychomotor task implies that supervisory ratings do not capture important dimensions of job performance. Why IQ validity decreases while job complexity increases: Today’s US economy is more focused on knowledge work and there is an increased use of technology in blue collar jobs.

In response, Sackett et al. (2023c) stated that the correlations with supervisor ratings are at the heart of much to most of what we know about the relationship between various predictors and job performance and that this criterion has been used for decades in meta-analyses. Regarding Hunter (1983), they stated that applying Hunter’s method of pooling incumbent data to estimate an unrestricted SD for studies in the newer GATB data set that used training criteria does not result in a restricted SD. Furthermore, the IQ measures were not used for selection in the GATB studies while trainees in the military studies had been selected in part based on their AFQT scores, and this means that range restriction is plausible for military studies but less so for the GATB studies.

Sackett et al. (2023c) finally argue that the increase in cognitive demands of jobs occurred along with increasing demands for interpersonal and teamwork skills, which they believe are unrelated to cognitive ability. This claim is odd, because there is evidence that intelligence affects teamwork performance (Kickul & Neuman, 2000; Devine & Philips, 2001). Furthermore, they have yet to prove that the importance of non-cognitive skill has increased to a greater degree than cognitive skill. Their story just doesn’t square with the data. There is no evidence that the relative importance of intelligence has diminished.

Kulikowski (2023) observed that Sackett et al. (2022) criticized Schmidt and Hunter’s (1998) study for using jobs with only medium complexity, whereas Sackett et al. (2022) did not control for job complexity as a moderator. This is surprising because the validity of IQ increases with job complexity (Cawley et al., 1996, Tables 7 & 8; Gottfredson, 1997, 2002; Lang et al., 2010). Kulikowski also wonders what is actually measured by employment interviews: personality, IQ, integrity, knowledge, all of these or something else? The IQ validity comes from many research while for other predictors, there is a relatively lower number of studies available, thus taking into account the crisis of reliability in psychological literature, the alternative of using non-cognitive variable is not justified, given that IQ predicts not only job performance but also job related learning and training performance.

A related issue is the cost. For IQ tests, the validity to cost ratio seems to be still very good and better than employment interviews. There is no reason to invest time and money in developing valid, reliable, and fair employment interviews when on a shelf there is a ready-to-use IQ test. Indeed, IQ test can be applied to many jobs from entry to managerial level and from simple to complex, whereas structural interviews must be adapted to given positions and occupations and might be inappropriate in many selection contexts (e.g. when candidates lack relevant job knowledge). IQ tests might be also conducted even by inexperienced recruiters but interview often demands from interviewers not only substantial knowledge in the interview domain but also self-discipline and reflexivity about their prejudices to conduct them fairly, validly, and reliably. It is not uncommon for two interviewers to reach different conclusions about the same applicant. In light of the many errors and cognitive biases (Kahneman, 2012), IQ tests remain the fairest method.

3. The choice of criterion (dependent) variable matters

In light of the revised estimates of interrater reliability of supervisor ratings of job performance of .46 by Zhou et al. (2024), Sackett et al. (2024) reconducted a meta-analysis for studies published between 2000 and 2021. One important focus is the comparison between overall performance and task performance.

This is because modern conceptions of job performance view it as multifaceted, including task performance, organizational citizenship, and the avoidance of counterproductive work behaviors, while earlier work such as Schmidt & Hunter (1998) had a narrower definition of job performance, namely, task performance. This could be important because Gonzalez-Mulé et al. (2014) found much stronger relationships between intelligence and task performance than between intelligence and citizenship or counterproductive behavior. One would expect a larger correlation between IQ and narrow performance than between IQ and broad performance.

However, the result shows here that overall performance ratings (ρ=.22) resulted in correlations comparable to those obtained using task performance ratings (ρ=.23). The authors do not have detailed information about the domain covered by overall and task performance and thus could not explain this finding. They suggest that the changing nature of work requires a broadening of the definition of performance, and the broad definition of performance explains the diminishing effect of IQ on performance. Their story is contradicted by their own finding, however.

Other findings are worth noting. Samples using data from multiple jobs produced identical correlations as samples using data from single jobs. Concurrent studies produced correlations (ρ=.22) similar to predictive studies (ρ=.21). But by far the most important finding is the following: samples using objective criteria produced higher validity (ρ=.38) than samples using supervisory ratings (ρ=.21).

One very odd finding is that the job complexity, measured with the component “Working With Information” from the O*NET variable, correlated .00 with IQ validity, which is inconsistent with prior research. One statistical artifact that could explain away such a result is range restriction, but they found no evidence of range restriction with respect to this job complexity variable. They suspect this is because older studies were based primarily on manufacturing jobs, which have become much less common in more recent studies.

Hambrick et al. (2024) conducted a meta-analysis based on cross-sectional studies. Unlike Sackett et al. (2022) they do not use global supervisory ratings because they may reflect not only an individual’s job-specific performance, but also non-skill factors such as organizational citizenship behaviors. They use instead hands-on job performance protocols because they are specifically designed to measure individuals’ knowledge and skill in specific job tasks.

In light of Sackett et al.’s findings, they had a good reason to apply range restriction correction to the correlations between AFQT and hands-on job performance, since the ASVAB is primarily intended for young adults and the range restriction correction in the AFQT score from the ASVAB was based on a nationally representative sample of individuals in this age range (18 to 23 years).

The meta-analytic correlation between AFQT and job-specific performance (rc = .39) is substantially lower than Hunter & Hunter (1984) (.51) and slightly higher than Sackett et al. (2022) (.31). Additional findings are worth noting. The mean time in service correlated (r = .49) with mean AFQT score across Military Occupation Specialties (MOSs), suggesting that high IQ personnel stayed longer. The AFQT score and cognitive complexity across MOSs were correlated (r = .49), suggesting high IQs are selected for cognitively complex jobs. The variability in AFQT scores was lower for jobs with high cognitive complexity than for jobs with low cognitive complexity. By contrast, when conducting moderator analyses on the restriction-of-range-corrected correlation between AFQT scores and job performance, cognitive complexity had no moderating effect. It is unknown whether the validity would be similar for high complexity jobs, since in this study the job complexity ranged from low to medium.

The authors acknowledge that the ideal design is a longitudinal study. They cautioned that changes in selection standards and/or selective attrition of participants can lead to the false appearance of interactions supporting either the convergence hypothesis or divergence hypothesis.

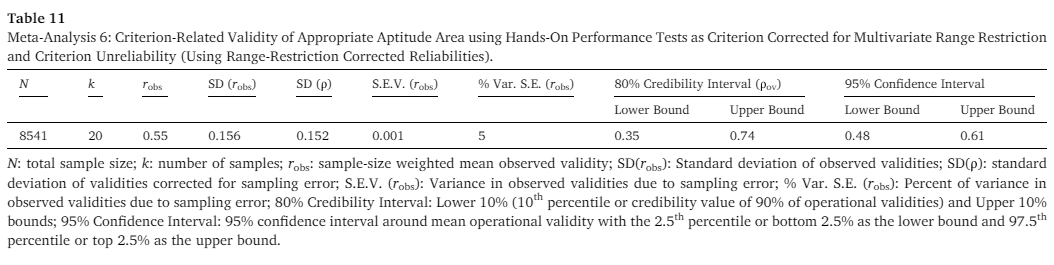

Cucina et al. (2024) conducted a meta-analysis involving hands-on performance test (HOPT) as the criterion variable. HOPT is a measure of job proficiency and task performance, as it requires incumbents to demonstrate their mastery of core job tasks while being rated by trained raters. Due to this condition of direct observation by trained raters, HOPT reflects maximal performance rather than typical performance. They focus their analysis on US military sample because IQ is likely used as predictor, with the either the ASVAB (which the authors weirdly call “appropriate aptitude area score”) or the AFQT (which is a composite of 4 subtests from the ASVAB) as cognitive test. Multivariate range restriction corrected validity coefficients were available for most of the samples included in this meta-analysis. This allows them to correct both direct and indirect range restrictions (RR).

After correction for RR and criterion unreliability, they found a validity of .44 for AFQT and .55 for ASVAB. This shows that a better measure of IQ improves validity. Although job knowledge has a validity of .63, one must remember that IQ strongly predicts job knowledge. The authors added a few comments. First, they could not use job complexity as moderators because data on job complexity ratings were lacking. Second, HOPTs appear to be measuring performance more objectively but they are very costly to develop and to administer.

Their finding of a higher validity confirms there is an element that supervisory ratings do not capture: a study by MacLane et al. (2020) found that opportunity to observe improves the association between IQ and supervisory ratings. In any case, the current debate is quite complex and there is likely more related research to come.

And indeed there is more. It seems that the predictive validity has declined and national norms are no longer unbiased for RR correction. Steel & Fariborzi (2024) analyzed four waves of the Wonderlic database (<1973, 1973-92, 1993-2003, 2004-2014). Their first study shows that occuptional applicant pool heterogeneity (based on SD) decreased across waves. The authors speculate this is due to increased education, driven by the education wage premium and credential inflation, as well as improved vocational counseling. Since people are now streamed toward occupations commensurate with their abilities, using national norms for RR can result in overcorrection (p. 7). This is because national norms may no longer reflect the more homogeneous applicant pools found in specific occupations. Indeed, the difference between national and applicant pool SDs grows over time (p. 8). The second study is aimed at evaluating whether the uncorrected IQ validity decreased over time (due to advanced education that causes homogeneous applicant pool) and whether correction for RR based on occupational applicant pools versus national norms changes over time.

The result is shown in Table 4. Their meta-analysis highlights: 1) that the uncorrected validity of IQ declined across waves, even though job composition changes had no impact on this decline, and 2) that the validity using RR correction based on occupational applicant pools decreases even further compared to RR correction based on national norms. At first glance, the validities for the Wonderlic are small-to-modest. This is however not surprising considering that the correlation between Wonderlic scores and academic performance is only .26 (Robie et al., 2024).

The study has several implications: 1) the excess supply of graduates and credentialism lead to inefficiencies in resource allocation, 2) the rise in education causes applicant pools to become more homogeneous and thus to diverge from national norms, 3) the validity correction for RR based on national norms becomes increasingly more biased over time.

References.

- Cucina, J. M., Burtnick, S. K., Maria, E., Walmsley, P. T., & Wilson, K. J. (2024). Meta-analytic validity of cognitive ability for hands-on military job proficiency. Intelligence, 104, 101818.

- Cucina, J. M., & Hayes, T. L. (2023a). Rumors of general mental ability’s demise are the next red herring. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(3), 301-306.

- Cucina, J. M., Wilson, K. J., Walmsley, P. T., Votraw, L. M., & Hayes, T. L. (2023b). Is there a g in gunslinger? Cognitive predictors of firearms proficiency. Intelligence, 99, 101768.

- Devine, D. J., & Philips, J. L. (2001). Do smarter teams do better: A meta-analysis of cognitive ability and team performance. Small group research, 32(5), 507-532.

- Gonzalez-Mulé, E., Mount, M. K., & Oh, I. S. (2014). A meta-analysis of the relationship between general mental ability and nontask performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(6), 1222.

- Hambrick, D. Z., Burgoyne, A. P., & Oswald, F. L. (2024). The validity of general cognitive ability predicting job-specific performance is stable across different levels of job experience. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(3), 437–455.

- Hambrick, D. Z., Oswald, F. L., Altmann, E. M., Meinz, E. J., Gobet, F., & Campitelli, G. (2014). Deliberate practice: Is that all it takes to become an expert?. Intelligence, 45, 34-45.

- Huang, J. L., Blume, B. D., Ford, J. K., & Baldwin, T. T. (2015). A tale of two transfers: Disentangling maximum and typical transfer and their respective predictors. Journal of Business and Psychology, 30, 709-732.

- Hunter, J. (1983). Test Validation for 12, 000 Jobs: An Application of Synthetic Validity and Validity Generalization to the GATB. Washington, DC: US Employment Service, US Department of Labor.

- Hunter, J. E., & Hunter, R. F. (1984). Validity and utility of alternative predictors of job performance. Psychological Bulletin, 96(1), 72–98.

- Hunter, J. E., Schmidt, F. L., & Le, H. (2006). Implications of direct and indirect range restriction for meta-analysis methods and findings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 594–612

- Kickul, J., & Neuman, G. (2000). Emergent leadership behaviors: The function of personality and cognitive ability in determining teamwork performance and KSAs. Journal of Business and Psychology, 15, 27-51.

- Kulikowski, K. (2023). It takes more than meta-analysis to kill cognitive ability. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(3), 366-370.

- MacLane, C. N., Cucina, J. M., Busciglio, H. H., & Su, C. (2020). Supervisory opportunity to observe moderates criterion‐related validity estimates. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 28(1), 55-67.

- Macnamara, B. N., Hambrick, D. Z., & Oswald, F. L. (2014). Deliberate practice and performance in music, games, sports, education, and professions: A meta-analysis. Psychological science, 25(8), 1608-1618.

- Platz, F., Kopiez, R., Lehmann, A. C., & Wolf, A. (2014). The influence of deliberate practice on musical achievement: a meta-analysis. Frontiers in psychology, 5, 96190.

- Oh, I.-S., Le, H., & Roth, P. L. (2023a). Revisiting Sackett et al.’s (2022) rationale behind their recommendation against correcting for range restriction in concurrent validation studies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 108(8), 1300–1310

- Oh, I. S., Mendoza, J., & Le, H. (2023b). To correct or not to correct for range restriction, that is the question: Looking back and ahead to move forward. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(3), 322-327.

- Ones, D. S., & Viswesvaran, C. (2023). A response to speculations about concurrent validities in selection: Implications for cognitive ability. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(3), 358-365.

- Sackett, P. R., Zhang, C., Berry, C. M., & Lievens, F. (2022). Revisiting meta-analytic estimates of validity in personnel selection: Addressing systematic overcorrection for restriction of range. Journal of Applied Psychology, 107(11), 2040.

- Sackett, P. R., Zhang, C., Berry, C. M., & Lievens, F. (2023a). Revisiting the design of selection systems in light of new findings regarding the validity of widely used predictors. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(3), 283-300.

- Sackett, P. R., Berry, C. M., Lievens, F., & Zhang, C. (2023b). Correcting for range restriction in meta-analysis: A reply to Oh et al. (2023). Journal of Applied Psychology. 108(8), 1311-1315.

- Sackett, P. R., Zhang, C., Berry, C. M., & Lievens, F. (2023c). Revisiting the design of selection systems in light of new findings regarding the validity of widely used predictors. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 16(3), 283-300.

- Sackett, P. R., Demeke, S., Bazian, I. M., Griebie, A. M., Priest, R., & Kuncel, N. R. (2024). A contemporary look at the relationship between general cognitive ability and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(5), 687–713.

- Salgado, J. F., & Moscoso, S. (2019). Meta-analysis of the validity of general mental ability for five performance criteria: Hunter and Hunter (1984) revisited. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 2227.

- Schmidt, Frank L., & Hunter, J. E. (1998). The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 85 years of research findings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 124(2), 262–274.

- Schmidt, F. L., Oh, I. S., & Shaffer, J. A. (2016). The validity and utility of selection methods in personnel psychology: Practical and theoretical implications of 100 years. Fox School of Business Research Paper, 1-74.

- Steel, P., & Fariborzi, H. (2024). A longitudinal meta-analysis of range restriction estimates and general mental ability validity coefficients: Better addressing overcorrection amid decline effects. Journal of Applied Psychology.

- Zhou, Y., Sackett, P. R., Shen, W., & Beatty, A. S. (2024). An updated meta-analysis of the interrater reliability of supervisory performance ratings. Journal of Applied Psychology, 109(6), 949–970.

Discover more from Human Varieties

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

What do you think of Richardson & Norgate (2015) arguing that the correlation between job performance and iq is overstated? Ree & Carretta (2022) argued that they don’t seem to understand how corrections for range-restriction works.

References:

Richardson, K., & Norgate, S. H. (2015). Does IQ really predict job performance?. Applied Developmental Science, 19(3), 153-169.

Ree, M. J., & Carretta, T. R. (2022). Thirty years of research on general and specific abilities: Still not much more than g. Intelligence, 91, 101617

I was extremely busy lately, that’s why I’m a bit late. Zimmer & Kirkegaard (2023) replied directly. In reality, the answer to your question can be found in this blog article. Indeed, the debate between Sackett and his critiques is fully packed in terms of information. In fact, if you read Zimmer & Kirkegaard carefully, you’ll find in their article that there is a great overlap in the references they cite and those Sackett et al. and their critics cite too. But also great similarity in the arguments put forth.

And the debate continues. Here’s what is happening: https://psycnet.apa.org/fulltext/2025-06323-001.pdf

Pretty much addresses it all: Job Complexity, Range Restriction, GMA validity coefficient decline and why. GMA is a big determinant of training success. Training success is needed for most jobs. This acts as a naturally occuring multi-hurdle selection system. It means that range restriction corrections should happen at the occupational level, not the national. This massively reduces the range restriction corrections. The more education needed to apply for the position, the more different the occupational group is from the national. Also, this leads to the multi-trillion dollar problem of credentialism.

Thanks. I read it yesterday, and this is incredible. I modified my article and added a discussion about your paper toward the end. Theoretically, that seems to make sense.