The first two of our admixture in the Americas papers have been published at Mankind Quarterly. To note, as I am skeptical of a behavioral genetic model, we advanced a genealogical one with an unspecified mode of inter-generational transmission. Similar models have been adopted in the economic literature (for example: Putterman and Weil, 2010; Spolaore & Wacziarg, 2015). For open access, we uploaded our papers to Research Gate. For the sake of transparency, the 18 supplementary files, the R syntax and the other data files have been made publicly available at Open Science Frame. The six commentaries are locked behind a paywall, but we covered most of the criticisms in our reply paper. If you can get a hold of them, though, they are well worth the reading. The conclusion of the reply paper sums up our general position:

We were pleased with the caliber of the comments. While incisive, none of them have inclined us to alter our conclusion concerning the R~CA-S hypothesis. But what now? First, more data. Specifically, indices of national cognitive ability need to be refined and more regional data needs to be located. In searching for this, it would be helpful to collaborate with researchers who are more familiar with Latin American datasets. Second, it would be worthwhile to further investigate a discriminatory model of individual differences using kinship designs and also to further investigate geographic models of regional differences, for example, using individual-level longitudinal data (to see if relocation to higher absolute latitude or colder regions has a positive effect on individual-level outcomes). Our models, in aggregate, are consistent with the view that contemporaneous cold weather and/or latitude is causally associated with positive outcomes, but an accurate assessment of the magnitude of these effects necessitates taking into account intergenerational factors. More generally, proponents of genealogical, discriminatory and geographic models have a mutual interest in building and making accessible databases that allow for the testing of these competing and probably co-occurring models.

As part of the reply we wrote another paper which focuses on the U.S. and will be published in the summer edition. Three related projects are also in the works.

….

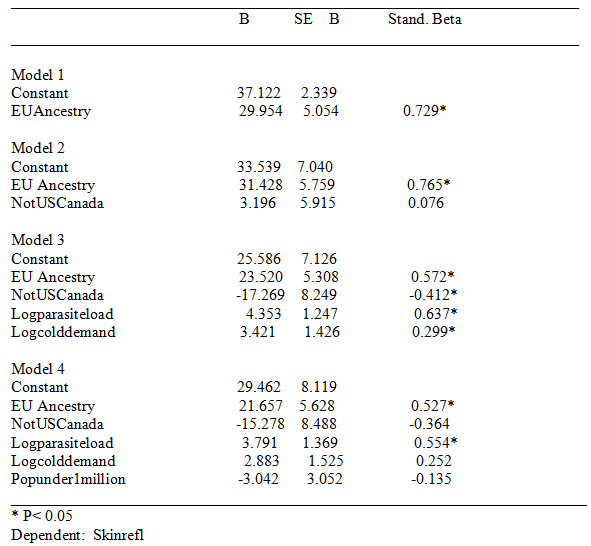

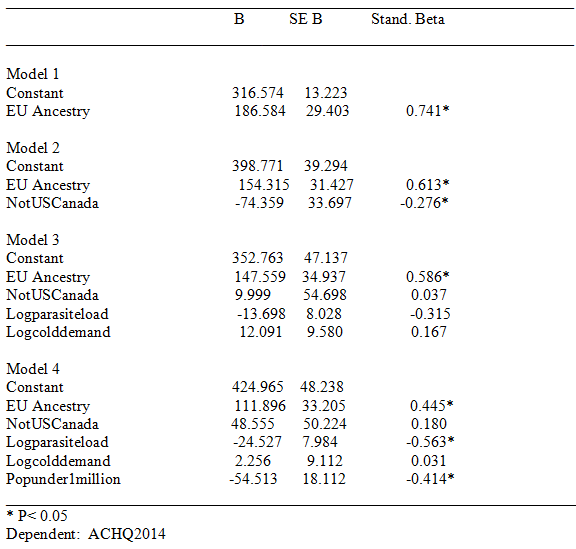

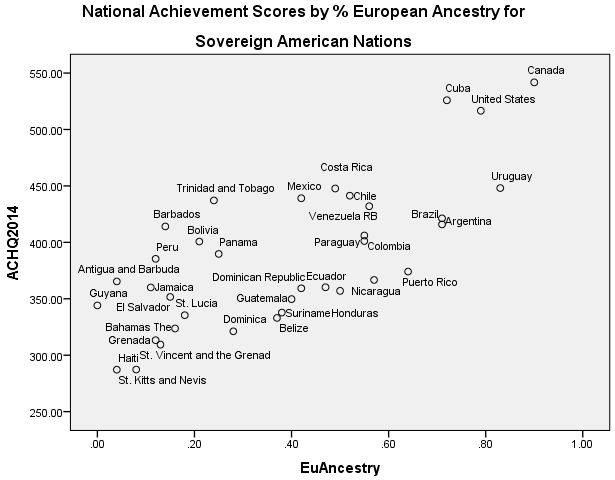

Fuerst, J., & Kirkegaard, E. O. W. (2016). Admixture in the Americas: Regional and national differences. Mankind Quarterly.

Ibarra, L. (2016). Statistics vs Scientific Explanation. Mankind Quarterly.

Flores-Mendoza, C., & Da Silva, J. A. (2016). Great effort, interesting results, but not everything is what it seems. Caution is required. Mankind Quarterly.

de Baca, T., Figueredo, A. J., & Garcia, R. A. (2016). Commentary on Fuerst and Kirkegaard: Some groups have all the luck, some groups have all the pain, some groups get all the breaks. Mankind Quarterly.

Christainsen, G. (2016). Admixture in the Americas: Social Differences as a Reflection of Human Biodiversity. Mankind Quarterly.

León, F. R. (2016). Race vis-à-vis Latitude: Their Influence on Intelligence, Infectious Diseases, and Income. Mankind Quarterly.

Pesta, B. (2016). Does IQ Cause Race Differences in Well-being? Mankind Quarterly.

Fuerst, J., & Kirkegaard, E. O. W. (2016). The Genealogy of Differences in the Americas. Mankind Quarterly.