Jason Malloy and I have individually collected a large number of papers and research reports from countries around the world detailing ethnic and racial differences. I have sent some of the stuff to Richard Lynn, lost a number of reports due to hard drive failures, and simply haven’t got around for various reasons (time, health, other priorities, etc.) to posting on the remainder. In response to an article by Chanda Chrisala, James Thompson recently suggested that it would be informative to look at ethnic differences in other American countries. As such, I will comment on a few studies from Canada and Brazil. Regarding Canada, there seems to be no published detailed ethnic data for the nation as a whole — though many reports discuss the Aboriginal/overall Canada gap. The country has a number of national longitudinal surveys which most likely contain the relevant variables, but as far as I am aware no has looked into the issue. Nonetheless, since the 1980s the Toronto public schools have published research reports which decompose math and reading pass rates by linguistic, ethnic, and racial background.

Author: Chuck (Page 3 of 6)

The discussion of the performance of African immigrants led by Chanda Chisala has been of unusually poor quality. As such, I thought that I might write a brief tutorial post on how to locate data and estimate differences in hopes that this will inspire better research practices and more rigorous debate. I will also elaborate on the Jensenist position and its predictions, as Chanda, and apparently many others, do not seem to have a good grasp of it at least in its quantified form.

A while back, in “People in the Future Will Not Look Like Brazilians”, Razib suggested that the great amalgamation will stall because those who are inclined to out mix will do so, taking with them their xenophilic dispositions. The suggestion prompted a commenter to question whether there was any evidence that preferences for (racial) endogamy had, as seemingly presumed by Razib’s argument, a non-trivial genetic component. Apparently, there has been very little genetically informed research on this or closely related topics. Nonetheless, I was able to locate eight studies based on five independent samples which provided heritability estimates for some measures of national, ethnic, or racial pride, preference, or prejudice. The study results are summarized in the table below.

I originally intended on including and briefly discussing these values in my “Ethnic/Race Differences in Aptitude” paper since therein I touched upon differences in Asian American subgroup performance (e.g., Table 15 and Table 17). Alas, I ran out of both space and my reviewers’ patience. Since the general topic continues to arise, I thought I might mention them, though. The 1996 and 2000 National Postsecondary Student Aid Studies (NPSAS 1996/2000), which were representative of the university populations at the respective times, contained both an “Asian origin” variable and a composite SAT score one, thus allowing for some investigation of subgroup variability. In expressing the differences, I used citizen/U.S. born White values as a reference for the SAT scores. Standardized differences were computed using the total group standard deviations, since population specific ones were unavailable. NA means that the sample sizes did not meet NCESDataLab’s cutoff for reportability. And negative values mean that the groups in question performed better than U.S. born/citizen Whites. As the confidence intervals — not shown below — were large for all of the Asian subgroups, results should be interpreted with caution. It’s notable that there were large U.S. born/non-U.S. born effects for both East and South Asians. The scores were for college students, so this might represent a foreign student effect (as opposed to a generation 1/generation 2+ immigrant one).

| NPSAS 1996 and 2000 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2000 | ||||||

| Nationality | non-Citizen | Citizen | All | Nationality | Not US Born | US BORN | All |

| Chinese | 0.01 | -0.66 | -0.44 | Chinese | -0.28 | -0.64 | -0.46 |

| Korean | -0.38 | -0.63 | -0.54 | Korean | -0.12 | -0.82 | -0.37 |

| Japanese | NA | NA | -0.79 | Japanese | NA | -0.20 | -0.06 |

| Filipino | NA | -0.17 | -0.13 | Filipino | NA | 0.03 | 0.12 |

| Vietnamese | 0.86 | -0.18 | 0.31 | Vietnamese | 0.61 | NA | 0.39 |

| Asian Indian | 0.47 | -0.96 | -0.43 | Asian Indian | 0.22 | -0.88 | -0.24 |

| Asian/PI (total) | 0.29 | -0.37 | -0.19 | Asian/PI (total) | 0.10 | -0.41 | -0.12 |

| White | 0.08 | Reference | 0.00 | White | -0.03 | Reference | 0.03 |

| Black | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.87 | Black | 0.74 | 1.00 | 0.96 |

Used the total group standard deviation

Source: https://nces.ed.gov/surveys/npsas/

Attempts to assess population aptitude from elite achievement go back to at least Galton. In Hereditary Genius, Galton used an estimate of the number of eminent persons produced by various ethnic and racial groups to quantify the differences between the means of these groups. Since his time, variants and refinements of this genre of analysis have become frequent. In “The Racial Origin of Successful Americans (1914)” Frederick Woods attempted to estimate ethnic achievement by counting and classifying the number of ethnic surnames in Marquis’ “Who’s Who” list. Lauren Ashe (1915) improved on the strategy by determining the representation of ethnic names in “Who’s Who” relative to that found in various U.S. city populations. In the 1960s, Nathaniel Weyl developed a variant of the “Who’s Who” surname method, one which relied on rare surnames, and in the 1980s he applied the method to National Merit Scholarship (NMS) lists (1), which record those high school seniors who obtained the top scores on College Board’s Preliminary SAT/National Merit Scholarship Qualifying Test (PSAT/NMSQT).

Chanda Chisala, a visiting Fellow at Stanford University, has developed what he considers to be a devastating argument against Jensenism (racial-IQ-hereditarianism). He develops this in his 2014 blog post, “Killing Jensen — part I“. Pithily put, the reasoning runs:

A reader asked if I might refer him to a cogent, while pithy, elaboration of the natural historian’s concept of race, an exposition which he might cite in future discussions. One of the most lucid articulations which I have encountered can be found in physical anthropologist Alice Brues’ (1913 –2007) book “People and Races” (1977/1990). Brues studied under Earnest Hooton, whose own concept of race was remarkably well articulated and coherent. In undergrad, she majored in philosophy (and psychology), a fact which might help account for the unusual lucidity of her discussion. In the seven pages of her first chapter, she says most of what needs to be said. And in the remaining chapters she makes the other necessary points. The first chapter is copied below both in PDF form and text. The discussion can be summarized as follows (with my notes added and paragraphs numbered). Continue reading

Below is an expanded and much improved rewrite of a draft which I had posted last year — improved thanks to the helpful commentary of Davide Piffer, Emil Kirkegaard, Kevin MacDonald, Peter Frost, Meng Hu, and others. As for the work, the intent was to clarify the concept of race, understood from the perspective of natural history, so to render the term which describes it inessential. It is hoped that the piece will also clarify the purpose of this blog, the focus of which is human varieties, of which races as constant varieties and natural divisions are but subtypes.

Fuerst, J. (2015). The Nature of Race: the Genealogy of the Concept and the Biological Construct’s Contemporaneous Utility. Open Behavioral Genetics.

Abstract: Racial constructionists, anti-naturalists, and anti-realists have challenged users of the biological race concept to provide and defend, from the perspective of biology, biological philosophy, and ethics, a biologically informed concept of race. In this paper, an onto-epistemology of biology is developed. What it is, by this, to be “biological real” and “biologically meaningful” and to represent a “biological natural division” is explained. Early 18th century race concepts are discussed in detail and are shown to be both sensible and not greatly dissimilar to modern concepts. A general biological race concept (GBRC) is developed. It is explained what the GBRC does and does not entail and how this concept unifies the plethora of specific ones, past and present. Other race concepts as developed in the philosophical literature are discussed in relation to the GBRC. The sense in which races are both real and natural is explained. Racial essentialism of the relational sort is shown to be coherent. Next, the GBRC is discussed in relation to anthropological discourse. Traditional human racial classifications are defended from common criticisms: historical incoherence, arbitrariness, cluster discordance, etc. Whether or not these traditional human races could qualify as taxa subspecies — or even species — is considered. It is argued that they could qualify as taxa subspecies by liberal readings of conventional standards. Further, it is pointed out that some species concepts potentially allow certain human populations to be designated as species. It is explained why, by conventional population genetic and statistical standards, genetic differences between major human racial groups are at least moderate. Behavioral genetic differences associated with human races are discussed in general and in specific. The matter of race differences in cognitive ability is briefly considered. Finally, the race concept is defended from various criticisms. First, logical and empirical critiques are dissected. These include: biological scientific, sociological, ontological, onto-epistemological, semantic, and teleological arguments. None are found to have any merit. Second, moral-based arguments are investigated in context to a general ethical frame and are counter-critiqued. Racial inequality, racial nepotism, and the “Racial Worldview” are discussed. What is dubbed the Anti-Racial Worldview is rejected on both empirical and moral grounds. Finally, an area of future investigation – the politics of the destruction of the race concept – is pointed to.

Keywords: natural division, race, biology

Contents

Introduction………………………………………..………………………………………………………………………………………..4

I. Biology – A Philosophical Clarification…………………………………………..………………………………..……..5

I-A. Existing Views: Confusions Abound

I-B. Biological Concepts in General

I-C. The Validity of Biological Concepts

I-D. Biological Kinds

I-E. Natural Biological Divisions

I-F. Races as Natural Biological Divisions

I-G. The Intraspecific Natural Division as Type of Biological Variation

I-H. The Natural Division as a Taxonomic Unit

I-I. Natural Divisions and Intraspecific Variation with Regards to the Subspecies Category

I-J. Biologically Meaningful Race Concepts

I-K. Biological Reality

I-L. Biologically Important Differences

I-M. Concepts of Biological Race

II. The General Biological Race Concept………………………………………………………..………………..……..25

II-A. The Genealogy of the Concept

II-B. Semantic Complexities and the Evolution of the Race Concept

II-C. Biological Race

II-D. What the Core Biological Race Concept Does Not represent

II-E. Races, Clines, Clusters?

II-F. Clarification on the Meaning of “Arbitrary” and “Objective” in Context to Natural Divisions

II-G. Regarding Different Definitions of Biological Race: What Races Need Not Be

II-H. Genomic-Genealogical Complications

II-I. Estimated Genomic Similarity: Some Ambiguity

II-J. Race: Mixed and Undifferentiated

II-K. Essential and Cluster classes; Fuzzy and Discrete Sets

II-L. Sociological Clarifications

III. The Ontology of Biological Race……………………………………………….……………………………………..……62

III-A. Other Defenses of Biological Race

III-B. Biological Races and Biological Reality

III-C. Thin Biological Racial Essentialism

IV. The Races of Man……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………81

IV-A. A Very Brief Historical Review

IV-B. Human Biological Races and Scientific Consensus

IV-C. Racial Classifications and Biological Race Concepts

IV-D. Traditional human Races

IV-E. THRs and Biologically Objective Races

IV-F. THRs and Migration, Intermixing, and Ancient Admixture

IV-G. THRs and Cluster Discordance

IV-H. THRs and Taxonomy

IV-I. THRs and Subspecies

IV-J. Are There Human Species?

IV-K. “Significant” Racial Differences

IV-L. Human Biodiversity (HBD) and Society

IV-M. Race and Intelligence

V. Critique of Anti-Biological Race Arguments………………………………….…………………………………….126

V-A. Anti-Biological Arguments

V-B. Biological Scientific Arguments

V-C. Sociological Arguments

V-D. Unnaturalistic Arguments and the Numbers Game

V-E. Onto-epistemology Arguments

V-F. Semantic Arguments

V-G. No-True-Race Arguments

V-H. Teleological Argument: The Future of Race

V.I. Can a Good Argument be Made Against (the) Race (concept)?

VI. A Troublesome Inheritance?…………………………………………………………………………………………………148

VI-A. The Social Destruction of a Biological Reality

VI-B. A Not So New Morality for Race

VI-C. The Moral Critiques: Arguments based on Outcome Differences

VI-D. The Moral Critiques: Arguments based on Racial Classification and Identity

VI-E. The Moral Critiques: Arguments based on Racial Favoritism

VI-F. The Moral Critiques: Arguments based on the “Racial Worldview”

Conclusion…………………………………………………………………………………………………………….……………………169

References…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………170

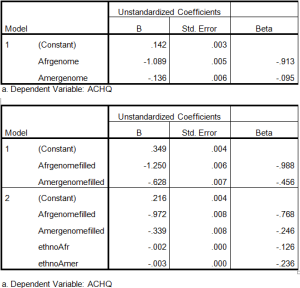

Emil and I set out to determine if regional variation in racial ancestry could (statistically) explain regional variation in cognitive ability. To keep things simple, we have limited focus to the Americas, which contain primarily trihybrid populations and for which there is a decent amount of admixture data. The results so far align with predictions. Both across nations and across regions within the U.S., Brazil, and Mexico, European ancestry positively correlates with regional-level cognitive ability. In contrast, both African and Amerindian ancestry negatively so correlates. The broader importance of the project is that it involves the construction of an expansive data set which allows for the statistical controlling of continental lineage and associated factors (genes + deep culture), ones which presently confound many analyses. This data set will hopefully allow one to uncover regional and national level factors which are not tangled with ancestry. They must exist. For example, we find that regional levels of European ancestry are associated with better outcomes in both the U.S. and Brazil but also that there is a substantial between nation effect that can not be explained by factors correlated with continental ancestry.

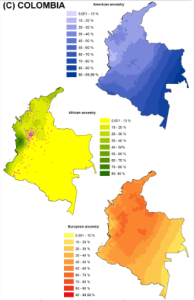

Here, I will discuss a new analysis involving Colombia. Colombia is marked by extensive spatial variation in  ancestry. The admixture map on the left copied from Ruiz-Linares et al. (2014) and the ethnic map on the right taken from Rodriguez-Palau et al. (2007) roughly capture the lay of the land. African admixture is concentrated along the Pacific and Caribbean coast, European admixture is highest in the north and central interior region, and Amerindian admixture is concentrated in the east and south. This ancestral variation allows for a test of our general model.

ancestry. The admixture map on the left copied from Ruiz-Linares et al. (2014) and the ethnic map on the right taken from Rodriguez-Palau et al. (2007) roughly capture the lay of the land. African admixture is concentrated along the Pacific and Caribbean coast, European admixture is highest in the north and central interior region, and Amerindian admixture is concentrated in the east and south. This ancestral variation allows for a test of our general model.

I computed the variables as follows:

Admixture : Estimating regional admixture for Colombia’s 32 departments plus the capital was not without difficulty since existent studies provide admixture data for only half of the departments. Problematically, specific estimates for the eastern and southeastern departments, which are reported to have high Amerindian components were not available. Nonetheless, we were able to construct three sets of admixture estimates. First, 18 departmental + capital estimates were taken from Salzano and Sans’ (2014) compilation. The ancestry ratios from Salzano and Sans’ (2014) two main sources correlated at 0.9, so we felt that using the combined estimates was justified. Second, missing values were filled in based on regional values and based on Ruiz-Linares et al.’s (2014) and Rodriguez-Palau et al.’s (2007) maps. For example, estimates for Caribbean-Pacific departments were averaged and used to fill in missing data for other departments in this region. In context to the U.S., this would be akin to filling in South Carolina values using the average of the Deep South ones. Third, admixture was estimated using ethnic identity data from the 2005 census in conjunction with average ethnoracial admixture percents as reported in all available studies. The ethnoracial admixture percents came out to as follows:

: Estimating regional admixture for Colombia’s 32 departments plus the capital was not without difficulty since existent studies provide admixture data for only half of the departments. Problematically, specific estimates for the eastern and southeastern departments, which are reported to have high Amerindian components were not available. Nonetheless, we were able to construct three sets of admixture estimates. First, 18 departmental + capital estimates were taken from Salzano and Sans’ (2014) compilation. The ancestry ratios from Salzano and Sans’ (2014) two main sources correlated at 0.9, so we felt that using the combined estimates was justified. Second, missing values were filled in based on regional values and based on Ruiz-Linares et al.’s (2014) and Rodriguez-Palau et al.’s (2007) maps. For example, estimates for Caribbean-Pacific departments were averaged and used to fill in missing data for other departments in this region. In context to the U.S., this would be akin to filling in South Carolina values using the average of the Deep South ones. Third, admixture was estimated using ethnic identity data from the 2005 census in conjunction with average ethnoracial admixture percents as reported in all available studies. The ethnoracial admixture percents came out to as follows:

The computation methods are detailed more precisely in the excel file.

Cognitive ability: For cognitive scores, the Colombian national SABER exam scores were used. The average of the 2003 and 2005 grades 5 and 8 math and reading regional scores strongly correlated with the average of the 2012 and 2014 scores (about 0.85). The scores were on different metrics, moreover standard deviations were not available for the 2003 and 2005 scores (given the source used), so, in the end, the 2012 and 2014 average scores were employed.

Other variables: 2010 HDI scores were taken from Machado (2011). Ethnic identity percents were taken from the 2005 census. Population was taken from the census via Wikipedia.

Results: I uploaded the excel file to facilitate future investigations. For the analyses reported below, in line with the general methods adopted for the meta-project, I excluded the capital and weighted by SQRT(population). Salzano and Sans’ (2014) admixture data showed only a weak negative correlation for Amerindian ancestry; this was because, as noted, data was missing for the most Amerindian parts of the country. When data was filled in, the association became significantly negative as predicted. It seems that the negative results are driven by the low scores in 5 districts (Amazonas, La Guajira, Guainía, Vaupés, and Vichada) all of which have high percents of self identifying indigenous and large reservations.

The results immediately above were replicated using the ethnic-admixture data.

Generally, European ancestry was non-trivially associated with cognitive ability (shown below) and with HDI (not shown). These results held regardless of which admixture variable was employed; they were largely driven by the strong negative association between regional outcomes and African ancestry. It is interesting that regional Amerindian ancestry was not associated with regional ability in the case of Salzan o and Sans’ (2014) admixture estimates. While on the national level, Amerindian ancestry negatively correlated with ability, as areas which were heavily populated by self-identifying Indigenous individuals did poorly, one might expect a more constant effect, one that would show up in Salzano and Sans’ (2014) restricted data set, which included only interior and coastal departments. The lack of association might have been due to the unreliability of the data, the specific samples analyzed, or the specific sampling of interior and coastal departments. Possibly, Amerindian ancestry is not negatively correlated with regional outcomes outside of largely indigenous regions. A determination of the matter will have to wait for the publication of more Colombian regional admixture data.

o and Sans’ (2014) admixture estimates. While on the national level, Amerindian ancestry negatively correlated with ability, as areas which were heavily populated by self-identifying Indigenous individuals did poorly, one might expect a more constant effect, one that would show up in Salzano and Sans’ (2014) restricted data set, which included only interior and coastal departments. The lack of association might have been due to the unreliability of the data, the specific samples analyzed, or the specific sampling of interior and coastal departments. Possibly, Amerindian ancestry is not negatively correlated with regional outcomes outside of largely indigenous regions. A determination of the matter will have to wait for the publication of more Colombian regional admixture data.

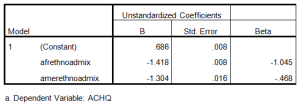

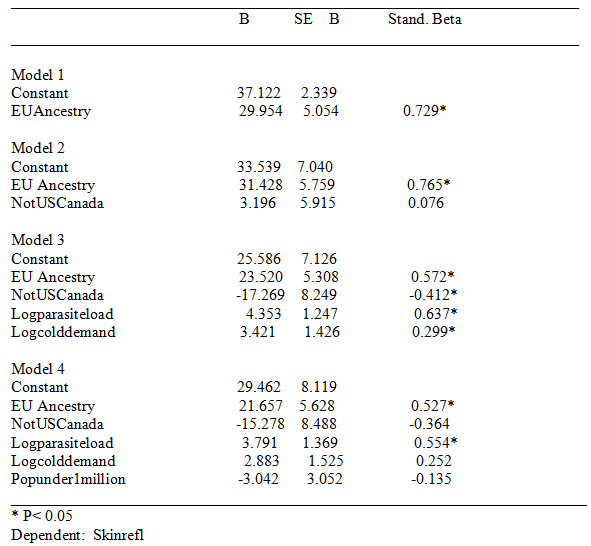

Following up with a previous analysis, I examined the cognitive variation across the whole of the Americas using a newly constructed data set. Files can be found here and here, with the latest versions provided on request. The analysis was restricted to sovereign nations, not e.g., departments such as Martinique or territories such as the Virgin Islands. Non-sovereign regions were excluded so to avoid an inter-nation x intra-national interaction and because international exam data was not available for these regions. The following 35 countries were included: Argentina, Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas The, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Barbados, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guyana, Grenada, Honduras, Haiti, Jamaica, St. Kitts and Nevis, St. Lucia, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Paraguay, El Salvador, Suriname, Trinidad and Tobago, Uruguay, United States, St. Vincent, Venezuela RB, and Canada. Eight regression analyses were run, using the following dependent variables:

- (Skinrefl) Skin reflectance.

- (AchQ) National Achievement Scores – this was an updated set provided by Gerhard Meisenberg during October of 2014.

- (NIQ) National IQ scores – these were based on Richard Lynn’s 2014 (work in progress) results and Jason Malloy’s 2013 to 2014 estimates, with adjustments.

- (AHQ) 1880 to 1930 birth cohort age heaping scores — this is a measure of education/numeracy.

- (logSciresearch) Log of scientific researchers from 2005 to 2012.

- (logGDP) Average of 1990, 2000, and 2010 log of World Bank per capita GDP.

- (Crimes) Violent Crime rates.

- (HDI2012) 2012 Human Development Index scores.

The following independents were included:

- (relativeEu) European Ancestry percent — the percent of European ancestry out of the percent of European + Amerindian + African ancestry. (For a discussion of this variable, refer here.)

- (notUSCanada) Not US or Canada — whether the region was not US or Canada.

- (logparasiteload) Log Parasite load — the log of the 2004 WHO parasite infections per 100,000 for each country.

- (logColddemand) Log Cold demand — the log of Van de Vliert’s (2013) cold stress scores.

- (PopUnder1million) Population under 1 million — whether the country’s population was under one million.

Simple correlation analysis demonstrated that ancestry, cold weather, and parasite load intercorrelated. This situation renders difficult the isolation of causal associations. To illustrate, skin reflectance was set as a dependent with Eu ancestry, cold weather, parasite load, population under 1 million, and not US and Canada as independents. The correlation between Eu ancestry and skin reflectance is clearly mostly genetic in origin. To the extent that the association between ancestry and skin reflectance is mediated by other variables, it is suggested that these variables co-vary with causal effects related to genes (and thus that controlling for them controls for ancestry related causal effects). Regression results are shown in Table 1, below. Generally, parasite load and cold weather seem to partially index ancestry effects. Parasite load is a particularly problematic “environmental factor” because it significantly correlates with STD and HIV rates (at 0.47). Yet the spread of HIV throughout the Americas, in the ’70s and ’80s, was subsequent to the origin of cognitive ability differences, which, in the form of national age heaping rates, were already present in the 1800s. Thus, STD and HIV rates and with them parasite load are, to some extent, consequent of cognitive ability differences.

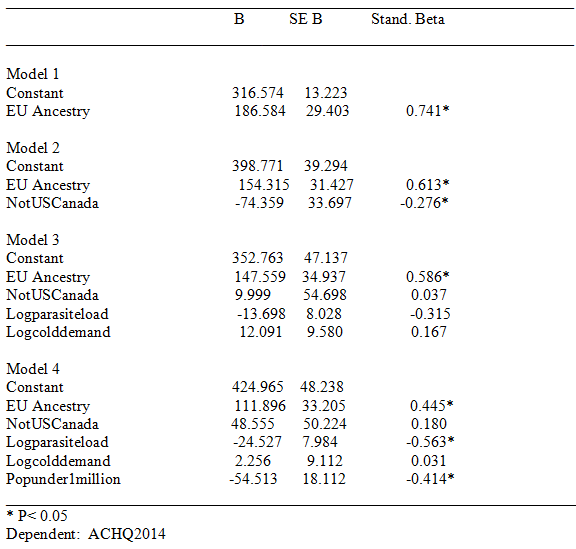

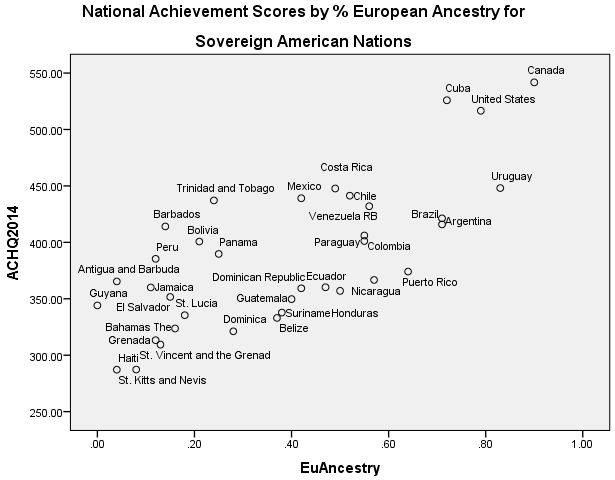

Results will not be discussed in detail. The data file is made freely available; readers can run the analyses as desired. Generally, European ancestry was a robust predictor of lower rates of violent crime, scientific activity, and achievement scores, and achievement plus National IQ scores. (For national IQ alone, in the final model, none of the predictors were significant; this was because the NIQ sample had many missing values.) In contrast to cognitive ability and the other mentioned indexes, European ancestry was generally not significantly associated with GDP or Human developmental indexes. The results for National achievement scores are shown in Table 2, below; a regression plot is shown in figure 1.

Table 1. Regression Results for Skin reflectance

Table 2. Regression Results for ACHQ2014

Figure 1. National Achievement Scores by % European Ancestry for Sovereign American Nations